In December 2024, over 500 girls faced mass FGM during the December holidays in the Kuria region, straddling the Kenyan-Tanzanian border. This marked the largest reported mass cutting in Africa, revealing a stronghold of resistance against FGM eradication.

The Frontline Response: A Race Against Time

Since June 2024, #FrontlineEndingFGM has been collaborating with five grassroots organizations and the Tanzanian government to deploy five Born Perfect Women’s Caravans across Tanzania, implementing our proven three-step solution to end FGM. However, despite the urgency, funding shortages have prevented intervention in critical areas like Kuria and Tana River. #FrontlineEndingFGM continues to advocate for donor support to reach all 22 FGM-prevalent counties in Kenya.

Vincent McWita, a veteran campaigner who has risked his life protecting girls in Kuria, said, “We lacked the transport, we could not help the police put the extra fuel in the cars that they needed – and the communities – seeing we could not intervene – became increasingly emboldened.” This region, known as Mara, is notoriously hardline, with campaigners facing attacks when attempting to intervene.

A Desperate Plea: The Caravan’s Mission

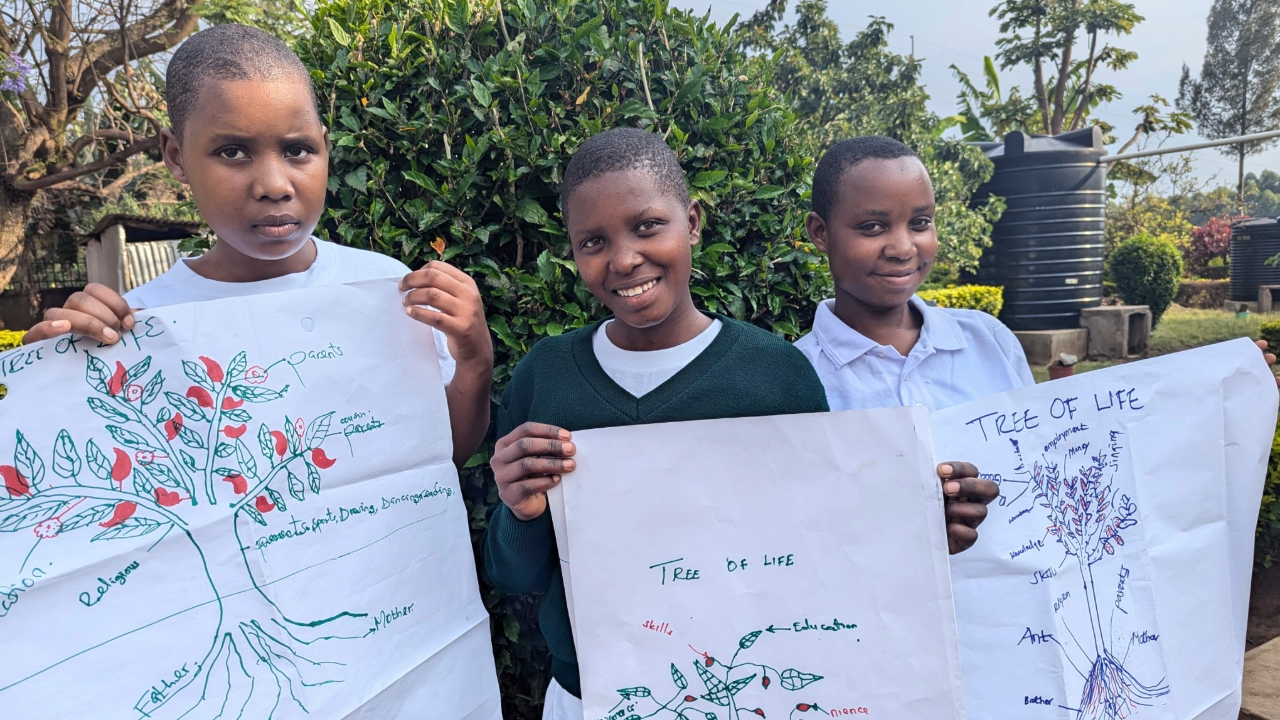

In a desperate attempt to halt the mass cutting, #Frontline campaigners planned a Born Perfect FGM Caravan, bringing together traditional leaders, clan chiefs, doctors, and survivors to journey from village to village. They urgently appealed for global support to prevent the impending mass cutting on the Kenya/Tanzania border. Safe houses had already been prepared for 500 girls, anticipating the scale of the crisis.

The Mara’s Dark Traditions: A Culture of Violence

Hardline traditionalists in this region perpetuate a culture of violence, where girls who die from FGM-related complications are abandoned in the Mara border forest. This practice highlights the extreme brutality and entrenched nature of FGM in this area.

The region is also known for its particularly severe forms of FGM, conducted during school holidays and preceded by a secret, deadly ceremony in September, where eight boys and eight girls are selected.

Valerian Mgana, a decade-long campaigner against FGM, revealed, “As well as being cut, they were also given special traditional herbs from the forest. If all 16 (8 boys and 8 girls) survived the secret ceremony, then the mass cut went ahead. If anyone of the 16 died, then the cut was postponed until the following year.” He added, “Even if all of those 16 survived the cut, the herbs they were given made many of them crazy. You saw them wandering in the street years later – still crazy after what had happened to them in that forest.”

Public Mutilation and its Aftermath: Community Complicity

In Kuria, the mutilation is a public spectacle, performed in front of the entire community. “It happened in an open space like a school playground with the whole community coming to witness the cut. The girls were lined up, and they sat on a cutting stone. The cutting of the external genitalia was done with a special knife in front of everyone. The cutting usually started at 6:00 am and was done by 9:00 am. Then the girls walked in a parade along the roads. Some of them were still bleeding. But the crowds were so big that you couldn’t get by in a car.”

Despite its illegality, police reluctance to intervene underscores the deep-seated cultural acceptance of FGM. Furthermore, a month after the cutting, girls and circumcised young men are forced into sexual encounters, leading to high rates of teenage pregnancies.

A Tanzanian government representative stated, “We couldn’t stop this. There was no point asking the police to intervene – as many of them were the same guys whose own daughters had been cut. It was a question of changing the culture, and that took time.”

Resilience and Resistance: The Fight for Survival

Amidst this crisis, Valerian Mgana and the Daughters of Charity in Masanga are preparing rescue centers for girls fleeing the cut. The impending mass cutting, publicly announced and meticulously planned, underscores the urgency of intervention.

Valerian Mgana emphasized, “We needed to go village to village as soon as possible with the Born Perfect Caravans – so people could watch the films, hear from the traditional leaders that we brought on side that this had to stop. We had made some progress over the last few years. Now many communities had stopped cutting out the external and internal lips and were only cutting out the clitoris – so we were making progress.”

The Daughters of Charity, who have been providing safe haven since 2008, continue to face down violent mobs. Sister Jacqueline Gbanga recounted a harrowing incident where Sister Efigenia’s bravery deterred an angry crowd.

The Human Cost: Stories of Survival and Loss

Isabelle, now a trained social worker, shared her experience of fleeing with her sister, but being unable to save their younger sister, Monica, who was forcibly cut. She also recounted the brutal mutilation of another girl, who required intensive care.

These stories illustrate the profound and lasting impact of FGM.

A Changing Landscape: The Impact of Climate and Tradition

In Kuria, girls who survive FGM are often married off, with the bride price significantly reduced due to climate change.

Vincent McWita explained, “Some years ago, the bride price for a girl was 20 to 25 cows, but now that price had gone down to 7 to 12 cows. Climate change meant people were losing their animals, and they just couldn’t afford that much anymore.”